Zimbabwe defies expectations and preconceptions. Travellers who come here despite its political and economic woes discover a remarkable, resilient and safe country with spectacular landscapes, myriad wildlife, cool camps and lodges, and top-class safari guides.

Its star attraction is the dramatic, bone-drenching Victoria Falls, the largest curtain of falling water in the world. Others include Hwange, the country’s largest national park, renowned for its huge herds of elephants. Magical Mana Pools National Park, a Unesco site on the banks of the Zambezi, offers camping, canoeing and walking. And Lake Kariba, a vast inland sea, has unforgettable sunrises with wildlife-rich Matusadona National Park on its shores.

Few visitors, however, make the journey to Gonarezhou. In the south-eastern corner of the country and an eight-hour drive or 90-minute flight from Harare, this remote national park hasn’t yet made it onto the travellers’ radar. But it soon will. With an incredible story of regeneration, conservation and hope for local communities, Gonarezhou is Zimbabwe’s rising star.

The ‘Place of Elephants’

Gonarezhou means ‘The Place of Elephants’, an apt name for a reserve that’s home to almost 11,000 pachyderms. Spanning 5035 sq km, the second largest national park in Zimbabwe is one of Africa’s last great wildernesses, raw and unfettered, a place of space and big skies, of ever-changing landscapes.

Crocs and hippos wallow in the sweeping Save and Runde sand rivers. The floodplains and forests of mopane, mahogany and giant baobabs are home to over 150 mammal species from prancing impala, wildebeest, warthogs and zebra to graceful giraffe, eland, buffalo and huge herds of elephants. Predators include lions, spotted and even brown hyena, and a staggering 12 packs of rare African wild dogs. Among its 400 bird species are majestic African fish eagles, spoon-bills and Pel’s fishing-owls, with the lily-strewn Tembwehata Pan and nearby Machaniwa Pan both classed as Important Birding Areas.

And at the heart of Gonarezhou stand the dramatic Chilojo Cliffs, almost 200m high and 16km long, in sandstone tiers of cream, pink and terracotta that glow gold at sunset.

Troubled past

Gonarezhou has a troubled history. In 1968, the Shangaan people living in the reserve were moved out to allow tsetse fly control; animals in the affected areas were culled. Gazetted as a national park in 1975, Gonarezhou soon became embroiled in civil wars, both Zimbabwe’s and Mozambique’s, with which it shares a border. During the conflicts, wildlife was caught in the crossfire.

With Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, the Shangaan wanted to return to their homeland but were refused as the government focused on conserving the park. Many went back regardless, including people from Mahenye village that borders the Park’s northern boundary. Poaching was rife and battles with rangers frequent and fierce.

Communities and Campfire

Out of this chaos, the concept of Campfire was born (Communal Area Management Programme for Indigenous Resources). Clive Stockil, a missionary’s son born and bred in Mahenye, and regarded as an honorary Shangaan, realised if communities owned the wildlife on communal lands and benefited from it, they would protect it. Following tense negotiations, limited hunting safaris were eventually allowed outside the park with an annual quota of two elephants: the meat and money went to the community.

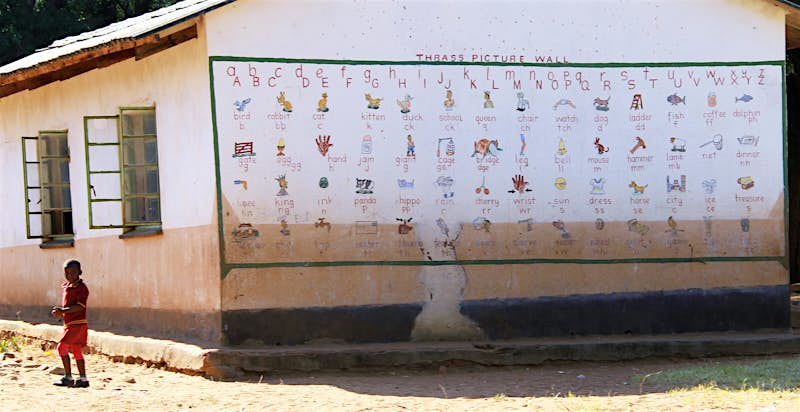

By 1983, the first school was built in Mahenye from the proceeds, and poaching dropped dramatically from one of the highest to one of the lowest rates in the country. Campfire became a blueprint for community partnerships in wildlife regions across Africa, and Clive became a renowned conservationist.

Today, after the troubles of the past, the people of Mahenye are settled there. Home to 6000 Shangaan living in traditional homesteads of mud and thatch huts with cattle kraalls, grain stores and chicken pens on stilts, the village now has a clinic, schools, boreholes and grinding mills provided through the Campfire initiative. And although it’s early days, they’re taking steps to create the new Jamanda Conservancy, having recently relinquished 121 sq km of their land abutting Gonarezhou for wildlife conservation and photographic safaris.

Gonarezhou’s new beginnings

During Mugabe’s disastrous economic management, the beleaguered national park struggled again with no resources to protect wildlife. In 2007, Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZPWMA) invited Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) to help restore the Park, with FZS initially supporting anti-poaching patrols, better training and improved infrastructure.

Ten years on, FZS and ZPWMA strengthened their partnership by forming the new Gonarezhou Conservation Trust (GCT) to manage the Park for 20 years: the Trust is transforming Gonarezhou into the thriving park it is today.

With wildlife populations booming, elephants, buffalo, lions and leopards make regular appearances. The only thing that’s missing is rhinos, poached to local extinction in the 1990s. Next year, however, all being well, GCT hopes to reintroduce rare black rhinos in a new conservation initiative to make Gonarezhou a Big Five (lion, leopard, rhino, elephant and buffalo) destination.

For all their success, however, conservation won’t work without communities on board. Villages that border the park live with elephants sometimes raiding their crops or lions killing their livestock. GCT is now closely involved with villagers through regular meetings to discuss such challenges. And through an education programme and workshops run by GCT’s Chilojo Club, people are learning about better protecting their crops and animals, about understanding animal behaviour and about conservation.

However, the greatest opportunity conservation brings is employment. GCT has opened a training centre for local people, a first for the area, and itself employs nearly 250 staff, 85% of them local.

Such opportunities are only likely to rise as Gonarezhou makes its rightful mark on the traveller’s radar and more visitors come to explore its wild, raw beauty.

Where to stay

Don’t expect masses of lodges and camps – what’s special about Gonarezhou is that it’s still a rare unspoilt wilderness.

The park runs campsites for self-drivers, from fabulous wild camping areas like Director’s near Chilojo Cliffs, where the only facility is a long-drop loo, to en suite tents complete with kitchens at Chipinda Pools. Unique manangas are a new style of camp with a light footprint, built and run by local women and replicating traditional homes, with a communal kitchen and dining area. Choose Masasani Mananga for daily sightings of elephants and antelopes coming to drink at the dam.

Beautiful Gonarezhou Bush Camp, a more upmarket camp, offers excellent private guiding with Ant Kaschula and five comfortable en suite tents overlooking Chilojo Cliffs and the river.

The closest lodge is Clive Stockil’s luxury Chilo Gorge on Mahenye’s communal lands. High on a cliff looking down into a spectacular gorge and the Save River, staff are predominantly local and the community receives lease fees and a percentage of its income.